“Temporary Insanity”: How A Cheating Congressman Killed His Wife’s Lover In Broad Daylight, Got Acquitted, and Created a New Legal Defense In the Process

During the 2016 US Presidential campaign, Donald Trump famously declared: “I could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose voters.” To his very minimal credit, Donald Trump has not literally tested this theory of trying to shoot someone.

But the same cannot be said for 19th Century Democratic Congressman Dan Sickles: a fellow New Yorker who–after years of cheating on his own wife–angrily shot and killed his wife’s lover in broad daylight, rallied the political establishment to his defense with some good old-fashioned misogyny and slut-shaming, and got acquitted for a murder that he proudly admitted to committing. In the process, Sickles made history as the first person to invoke the legal defense of “temporary insanity.”

Here’s a little bit of background on this sordid American tale.

History of Daniel Sickles

Daniel Sickles was born on October 20, 1819, to a wealthy New York City family. A state assemblyman, state senator, congressman, diplomat, Union Major General in the Civil War, and a Medal of Honor recipient, Sickles certainly had quite the illustrious career (aside from the whole “cold-blooded murder” thing).

Despite killing a man for sleeping with his wife, Sickles’ own womanizing was so infamous it earned him the fitting moniker “Devil Dan” Sickles.

For years, “Devil Dan” openly carried on a relationship with famed prostitute Fanny White. (That’s right, in the 19th century it was possible to be a “famed prostitute…” in New York City. Also, dude that is not the preferred nomenclature. “Successful Courtesan,” please.)

No fan of Victorian Era morals, Sickles delighted in bringing Ms. White to parties to the horror of high society guests. As a member of the New York Assembly in 1847, Sickles was censured by the opposition Whig Party for bringing said courtesan into the assembly chamber.

If that sounds bad, don’t worry, because…

In 1851, the then-32 year old Sickles began courting 15-year-old Teresa Bagioli, who he had known since she was a baby. Yikes.

The following year, Sickles married the pregnant Bagioli over the objections of her family. But even after tying the knot, Devil Dan the married man would continue his cheating ways. During a delegation to London, Sickles reportedly left his pregnant wife at home and instead took his favorite sex worker Fanny White to meet Queen Victoria.

Spurned, abandoned, and repeatedly humiliated by her cheating husband, young Teresa would find comfort in the arms of another man. A famous one at that.

The Phillip Barton Key-Teresa Sickles Affair

Philip Barton Key II was the U.S. Attorney/District Attorney for Washington D.C. He was also son of Francis Scott Key–famed author of the U.S. National Anthem “The Star Spangled Banner”.

In 1857, Devil Dan the cheating man became a Congressman. The same year, Congressman Sickles met Key at a late-night card game, and they became fast friends. Key, a widower, was later introduced to Sickles’ wife Teresa. Mrs. Sickle and Key would often accompany one another to parties and to the theater.

In the Spring of 1858, Teresa and Key officially began their affair. The pair would arrange clandestine meetings at a home Key had rented at Lafayette Square–which was down the block from the Sickles’ D.C. home. Teresa’s husband was apparently oblivious to the whole affair. But the secret began to unravel on the evening of February 24, 1859.

On that night, Sickles received an anonymous letter exposing the affair between Teresa and Key. The letter detailed how and where the pair were meeting, including that Key “hangs a string out of the window, as a signal to her that he is in and leaves the door unfastened, and she walks in…”

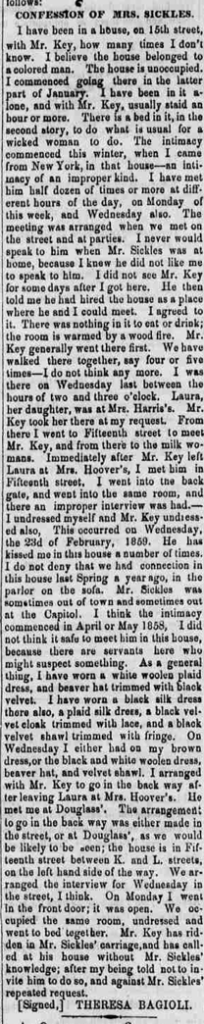

Despite having cheated on his wife for years, this news enraged Sickle, who confronted his wife for her infidelity. Sickles then pressured Teresa to write a humiliating letter where she admitted to having engaged in “intimacy of an improper kind” with Key, writing “I did what is usual for a wicked woman to do.”

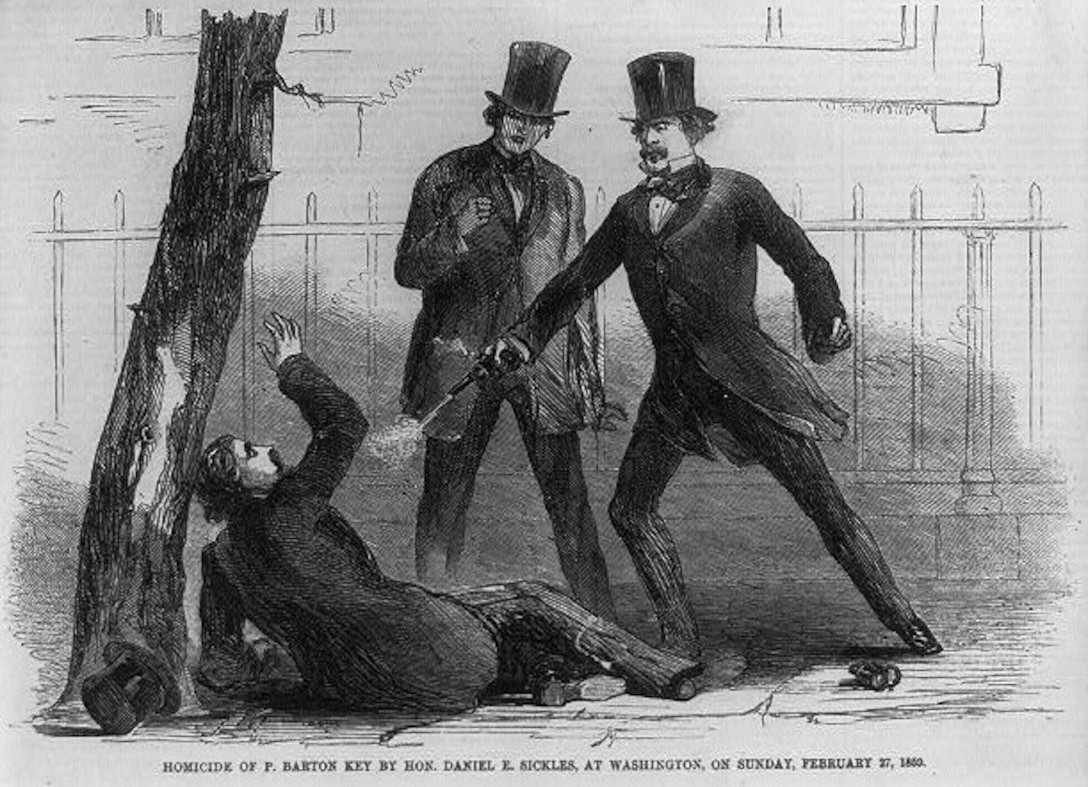

Three days later on February 27, 1859, the Congressman took his bloody revenge.

Killing Key

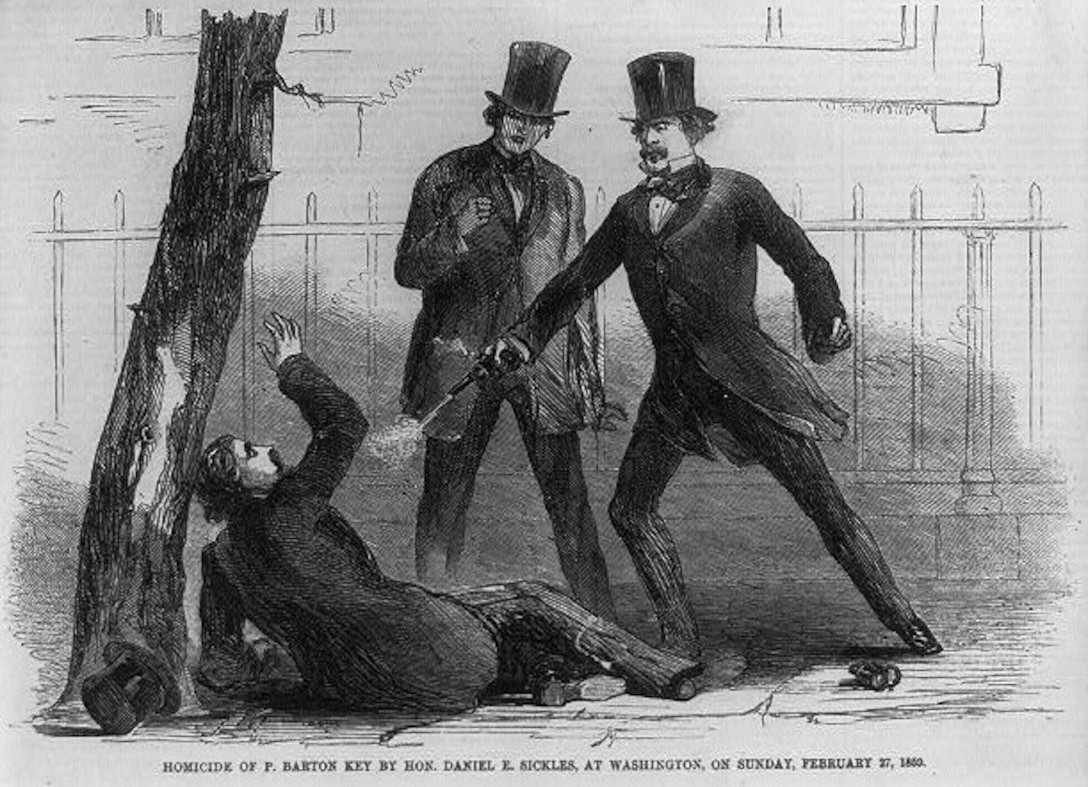

Upon seeing Key walking toward Lafayette Square–signaling for Teresa–Devil Dan ran to confront him. When the US Attorney saw the recently re-elected Congressman, Key extended his hand, expecting the encounter to be friendly. But Sickles–armed with two single-barrel Derringers and a revolver–did not come to talk.

Standing in full view of the White House, Sickles reportedly exclaimed: “You have dishonored my home and family.” Mr. Key–armed with only a pair of opera glasses to defend himself–was quickly overwhelmed by the Congressman, who proceeded to shoot his rival three times until he collapsed, dead. Sickles then walked to the house of a neighbor, US Attorney General Jeremiah S. Black, and surrendered.

Now, this seemed like an open-and-shut case. Sickles shot a famous US attorney in broad daylight, admitted to doing the crime, and expressed zero remorse for his actions. During a jailhouse interview, Sickles reportedly told the New York Tribune:

“[Key] has dishonored me, and we could not live together on the same planet.”

But Sickles would not go quietly. The Killing Congressman assembled an elite defense team that included Edwin M. Stanton, a well-connected D.C. attorney who would eventually serve as President James Buchanan’s lame-duck Attorney General and President Abraham Lincoln’s Secretary of War.

Some scholars believe that Stanton joining Sickles’ defense team was a sign that the Congressman not only had the full support of the Democratic Party, but President Buchanan himself.

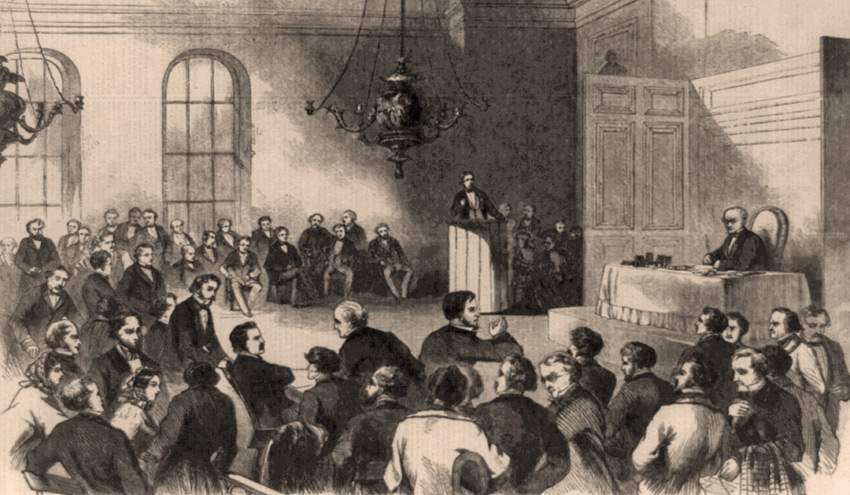

The Trial

At trial, Sickles’ lawyers unveiled an argument that had never been used in court–that Sickles was not legally responsible for the murder because the rage at his wife’s infidelity had driven him temporarily insane when the shooting occurred. Though the insanity defense had long existed, this was the first time anyone had invoked the defense of being only temporarily mad.

Despite Sickles’ well-known history of infidelity, Sickles’ attorneys made Teresa’s adultery the centerpiece of their trial strategy. Though her written confession was not admitted into evidence, the reputation of Teresa Sickles became collateral damage as her affair was documented in explicit detail.

Stanton told the court that Key had put Teresa on the road toward “the horrid filth that is common prostitution” and that “the death of Key was a cheap sacrifice to save one mother from the horrible fate.” Sickles’ defense team portrayed the Congressman as a hero who–while driven temporarily mad by his wife’s affair–had bravely stepped up to rescue this vulnerable woman who had been tempted into sin by the rakish US Attorney.

As audacious as that argument sounds, it made perfect sense in 1859. And that’s precisely what won the day in the court of public opinion and the actual court. After a 20-day trial and just over an hour of deliberation, the jury found Sickles not guilty of his purported crime of passion.

When the not guilty verdict was read, the courtroom reportedly burst into thunderous applause. (Because, you know, 1859.) By the time the defense had rested, most Washington newspapers were praising Sickles for “saving all the ladies of Washington from this rogue named Key.” Others were appalled.

“We regard this as a most mistaken and most mischievous verdict — a sanction to the substitution of violence and vengeance for reliance on the regular and orderly redress of grievances through the instrumentality of law,” the New York Tribune editorialized. “It is a verdict which carries this country a long stride backward toward the age when Might was Right, and all wrongs were redressed by the red hand, or not at all.”

The Modern “Crime of Passion” Defense

Even though this case happened over 160 years ago, it remains an egregious example of hypocrisy, double-standards, and antiquated sexism. But given that we still have all of these things in 2023, it begs the question–would the case turn out differently if it were tried today?

Answer: probably.

When Sickles invoked the temporary insanity defense, it served as a complete defense to murder. But if a case with these facts went to a jury today, there would be little chance that the Congressman would have been acquitted.

Under US law, a “crime of passion” refers to a killing that is committed in the “heat of passion” in response to a sufficient “provocation.” The “provocation” element usually arises in cases where an individual finds his or her spouse in bed with a lover, snaps, and proceeds to immediately kill one or both of them. The crime of passion defense does not completely absolve the defendant for the killing, but invoking the defense can reduce charges from premeditated first-degree murder to a less-severe second-degree homicide or even manslaughter.

There are two requirements for invoking the crime of passion defense:

- the provocation must be the type that would inflame the passions of a “reasonable person”; and

- there must not have been any opportunity for the accused to have “cooled off” or regained self-control between the provocation and killing.

However, if the accused had the opportunity to cool off first, then the crime of passion defense fails to overcome the presumption that the murder was premeditated.

In Sickles’ case, he learned about his wife’s affair on February 24, 1859, waited three days, approached Key, then shot Key dead in broad daylight right after proclaiming in essence ‘I am going to murder you, and this is the precise reason why I have planned to murder you.’ This was clearly premeditated.

Also, Sickles’ long history of open infidelity and spurning his wife (like bringing a courtesan to meet the Queen of England) is further evidence of his lack of commitment to his spouse and that his reaction to the provocation was not reasonable.

I will say one thing: when people went a-murdering in the 19th century, at least they put on their best suit and top hat. Kind of like how we used to wear suits to fly on airplanes, but now people fly in sweats and remove their shoes/socks/dignity.

I’m just saying, if you absolutely must murder someone, have a little class when you go out into the world.

Legal Disclaimer: Don’t commit murder, however well or poorly you are dressed.